A warning that this piece contains references to guns, violence, suicidality, mental health issues and filicide.

This piece is truly not for everyone. It might not be for you. Come back another day, if today you’re feeling sensitive.

I’ve written and spoken on violence within Truth 2x2 and fundamentalist (mainly rural) communities for a while now, in women's magazines predominantly. Every time I’ve published a piece; I’ve carefully crafted around disclosing too much of my own story. Underpinning my writing on violence in these communities is a very real, lived experience.

If you’ve been around here awhile, you’ll know I was trying to protect my own family. I know the experiences the women in my family survived. I have a deep respect and understanding that their lives were difficult. I have never wanted to cause more harm or distress by naming what they’ve done to contribute to violence.

However, this piece is to say: I’m done. I want to talk specifics about the violence.

I grew up surrounded by violence, coercion and abuse. Some of it was perpetrated by women. That is a difficult and extremely nuanced conversation in a culture where men perpetrate the majority of violence, and where the manosphere likes to accuse women of equal levels of violence as a deflection technique. I want to be clear here – my talking about women who abuse should not be used to deflect from the very real issue of men's use of violence.

What I'm writing on here is nuanced – these women are abusing in the context of high control, high demand, cult communities. These communities allow (encourage in my opinion) women to use violence on their children.

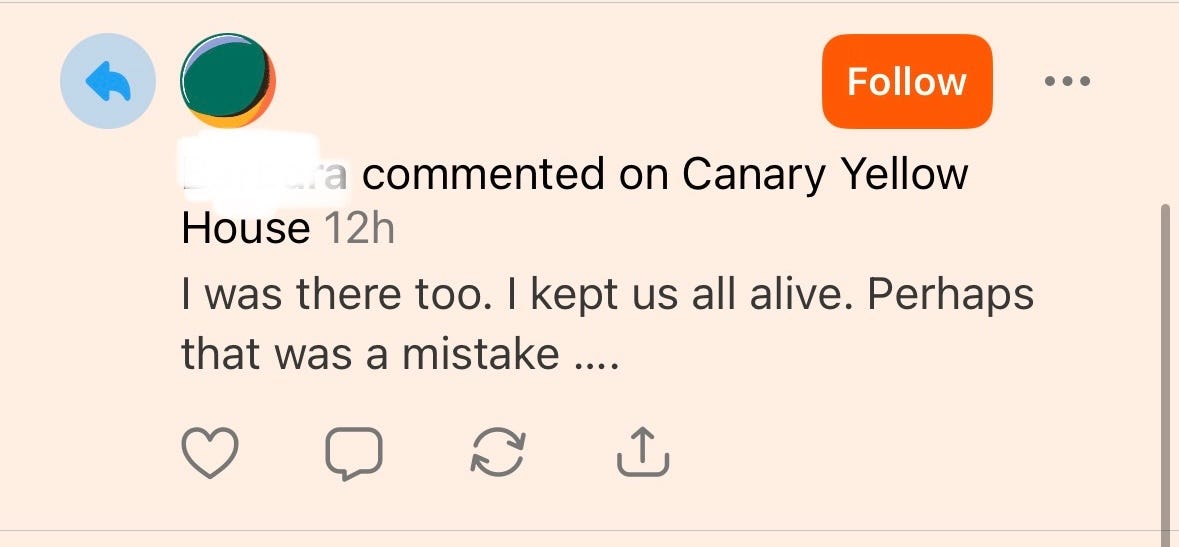

Violence and abuse by the women in my family still flares up in my life. Often after I’ve had something published in mainstream media, one or more of them will reach out in email or via DM’s on social media, with paragraphs of vitriolic hate mail. Right now there is content galore to flare them up – a Decult documentary released which includes me. A Victorian inquiry into cults and fringe groups, which I’m playing an active part in. They can find information about me and my work unsolicited in their social media feeds, and its quite upsetting for them, it seems.

What they could do is be proud when this information about me, crosses their paths. They could think ‘How amazing is it that one of OUR OWN is breaking intergenerational cycles?’

Instead they lash out.

I’m liberal with the delete button. I try not to read the messages anymore. They’re not worth absorbing – nothing in there tends to be constructive. It’s hate. It’s often death threats or suicide threats; often threats to harm people I love.

I went to the police once, back in 2011. One of my aunts threatened to harm my pet and burn my house down (she later claimed to have been on stilnox and not to have remembered sending the email). Police told me to go home and sort it out myself as it was a ‘family issue’ and not something they wanted to get involved in. That experience, amongst other unfortunate experiences with the ‘justice’ system means I don’t bother with reporting most issues to police. It’s a last resort.

A part of me knows that police would probably respond differently if I went back now with similar information. I still avoid them – I don't feel comfortable or trusting enough to take my family through these legal processes. I grew up in a 2x2 culture that deeply distrusted authorities, and then I lost my father to the justice system – there are deeply held reasons I don’t report.

It brings to me to today: This week my mother has been online and left some inflammatory and violent messages on my work.

It's not possible that her peers haven't seen it – its right there – under their noses on social media platforms. How many of her peers do you think have reached out to me? How many of them do you think have commented on some of her statements, said ‘That seems a bit abusive, should you be saying that to your daughter?’

None. The silence is deafening.

That’s Truth 2x2 culture right there in action.

Someone behaves inappropriately; everyone ignores it. Everyone looks the other way.

Thats how abuse flourishes in our culture. Silence. Permissiveness.

No one wants to be the one who speaks up in Truth 2x2 culture. Sweep it under the rug, hope it goes away.

My mother obviously has serious mental health issues, but she won’t accept it let alone get help for it. I once mentioned in a news article about me having to navigate her precarious mental health as a child. She contacted me to say she didn’t have any mental health issues and was offended I’d mentioned it.

About a decade ago I wrote a piece about my first memory of my mother’s precarious mental health. An editor commented that the story seemed ‘like a lot, a bit confronting’ - so I shelved the piece and never published it or pitched it.

I was ashamed that I’d written it, held a fear that I wouldn't be believed for how bad and deep the abuses went at the hands of my mother.

Today I’m setting that piece free here.

You can choose to believe it, or not.

Doesn’t she know the baby is teething?

My mother liked to spit words at me. Words like ‘selfish’ ‘boisterous’ ‘stubborn’ ‘ungrateful’. I was always ‘too curious’ and ‘setting the wrong example’. I didn’t hear many affirming things about my personality. The first time I heard someone say something positive about me, I held onto those words for decades.

I was seven.

I don’t know how the nurse came to find us. We lived 15 kilometres off the highway to Bourke, down a dirt road with three rough farm gates to open before the house. Somehow, a nurse had turned up to our farmhouse to talk to my mother.

I realise now it was probably a counsellor or a mental health worker, sent to check on her. No one accidently found our house, 60kms from the nearest town. It was the mid 1980’s – did mental health nurses even exist then? I don’t know the answers about who that nurse was or where she came from.

The week before my father had taken her to Dubbo and pushed her into a doctor's clinic, pleading with her to ‘get help’. I don’t remember what ‘help’ she needed or what the problem might have been.

She was always telling us ‘Don’t tell anyone anything about our lives, they won’t understand’. I’ve no doubt she didn’t tell the doctor much in that clinic that day. She must have told them something though, for them to send a nurse all that way to see her.

That day my father had dropped her at the medical clinic in the back streets of Dubbo, a two-and-a-half-hour drive from our farm, and taken us back up to the Wingewarra Street social security office.

While he went inside to hustle an advance on our social security payment, I sat in the stuffy car, in charge of the kids. I was seven, the youngest was a baby, maybe verging on a toddler. Sometimes he takes us into the social security office with him, says you get more in advance if you have the kids with you. But that day. I’m left in the car with the grizzling, teething baby.

I’m used to being the one they leave in charge of the littler kids. Along with ‘selfish’ they also call me ‘the responsible one’. I guess you could consider that a back handed compliment.

You’re a selfish kid, but also we’ll rely on you to parent all the younger kids. Cults and Fundamentalist Christianity is like that – quick to make oldest girls into pseudo-parents and shame us when we push back on it.

I’ve got a seven -year-old child here beside me now as I edit this story, he can barely tie his own shoelaces, let alone care for a teething baby.

At seven, I'm used to absorbing my mother's moods. I’m used to reading her body language and knowing when the right time is to whisk the little kids away, outside. I’m hypervigilant, I know how to disappear up a tree or behind a shed when she’s lashing out. I know how to say ‘I did it’ when she’s targeting one of the younger kids for something trivial – absorb the whacks of the wooden spoon, protect the little ones.

Back to the nurse and her fancy Land Cruiser, arriving unexpectedly down our corrugated dirt road. I’m outside playing games and entertaining the kids. I’ve read my mother’s mood that day and decided the best place for us is outside. I’ve set the other kids up in a cubby house and I’m busy making myself a washing line.

I’ve recently seen my Nan make a new washing line out of few stray posts and some fencing wire, and I’ve decided our backyard cubby house could do with one of those. I’ve spent the morning wandering around the farm collecting old posts and pieces of wire. I’m ready to start construction.

My Nan and Grandad are living on a nearby farm, in what can be best described as a humpy. Its a caravan parked inside a machinery shed, with a dirt floor. Nan ‘makes do’. She gives that skill to all of us. She teaches us: Don’t ask too much, don’t be demanding, just ‘make do’.

My father is away in a shearing team near the Queensland border. He goes away all week, comes back late Friday nights. He sticks around for Sunday Morning Meetings, then heads back out to the shearing team. He leaves my mother there, on the farm alone with the kids. It’s not good for her mental health. She projects something different to everyone off the farm though. Here - we know her moods and her behaviour. As soon as she hits the highway to town though – she’s a different person. Pious. Controlled. Demure. Kind. Intelligent. A talented musician.

We have limited contact with people outside The Truth 2x2s. Mostly we keep to ourselves and our family and community. My mother tightly controls us in public – neatly ironed dresses, perfect white socks, perfect clean shoes (no easy feat in the red sand we live in). We dare not move or say a word out of line in public, we know she carries a wooden spoon in the glove box and another in her handbag. She’ll use it liberally. When no one else is watching.

Friends of the Truth 2x2s must see it – they must see her emotional instability, her inability to cope with her children. At the very least, our family must see it. The many cousins, aunts and uncles who flow through our family farms, they must see it.

They look the other way, I know that now. They look the other way.

They still look the other way.

My mother tells stories that scare me. We’re not long out of a big drought, and stories have circulated about a woman who lined her kids up against a rainwater tank and went to shoot them, desperate that there was no money and no way off the farm. Why does she keep telling that story? That story bothers me and so does the numerous times she keeps telling it, in front of the little kids. Its unnerving. I don’t trust her. She doesn’t feel safe.

She often has raging arguments with my father on weekends. She gets in the car, drives off into the scrub for hours on end. It’s never clear if she’s coming back, or where she’s gone. Our cars are notorious for breaking down or running out of petrol. I live on a knife edge, worried about where she is and if she’s coming back. And has she taken one the guns?

There are guns. A lot of them. She has one near the door for snakes, and my father has a cache of them scattered about the place. It’s a world before John Howards gun safety laws.

Back to that nurse. She parks her fancy Land Cruiser and makes her way inside to see my mother.

I don’t think my mother is expecting her. My mother doesn’t really like visitors, prefers to meet people outside our farm. We don’t have guests here to our tumble down – barely-weatherproof farmhouse.

I’m deep in construction mode for my clothesline, trying to work out how to get these posts to stay upright in the red sandy soil. Time passes. The nurse comes outside and tries to strike up a conversation with me.

I’m a bolshy kid, tough, with a lot of opinions. But I’m shy with strangers, especially Worldly people. The world outside our farm is scary – I can’t read Worldly people the same way I can read my mother. I withdraw into myself, stay quiet.

She was persistent, that nurse. She sat down next to me in the red sand and kept trying. ‘What are you building?’ ‘Is Dad away working this week?’, ‘Who is looking after the baby? ‘Do you think the baby is hungry?’

I thought she was annoying.

I thought it was obvious I was building a washing line. I was sure my mother would have mentioned that my father was away working. And mostly, I was offended that she thought I couldn’t manage the baby, who had mushed up the last teething rusk all over their face and was squealing because they had new teeth –everyone knows that’s what teething babies do, don’t they?

Then she said something that blew my little mind: ‘You’re very creative and inventive, aren’t you?’

I couldn’t believe someone said something so nice about me!

I held on to that for years, so proud and pleased that someone had something positive to say about me.

-----

A year or so later my mother gets us off the farm, into the town 60kms away, to the unhappy canary yellow house I wrote about earlier. It’s a feat, know this. It’s a feat that she got us off that farm without lining us up next to a rainwater tank, like that woman she prolifically told us about.

She leaves my father to run his farm, sets herself up with her own life and her own job. It was the best thing she could have done for her mental health.

Her decision to get a job paved the way for me to see women who could work off the farm, could build their own lives. I’m not the only Truth 2x2 girl who grew up grateful for her example – she taught a whole generation of us McConnell and Kemp girls that it was possible to work outside the farm and home.

She taught us that women could be independent, at a time when Workers like Clyde McKay (who later became Australian Overseer) was mooching around our farms for weeks on end, telling us from the platform (and the dinner table) that women belonged in the home, that their role was to be subservient.

I still get messages from women who say she inspired them to have careers. She paved the way for lots of Truth 2x2 girls – but truthfully, it was at my expense.

There is the uncomfortable fact that her working long hours left me with even more responsibility. It meant even more parentification for me.

This comes with juxtaposed feelings. I think the kids were safer with me.

But I was just a kid myself. I wasn’t a good enough parent for them.

Her being out of the house meant less abuse and violence towards us – that much is true. While she was working, she wasn’t threatening suicide on us. It was something she did regularly when the house wasn’t tidy, the washing not done to her standard, the kids’ homework not perfect enough.

While she was at work, we were safer. While she had money, the car ran consistently, the bills got paid. We stopped having to hustle advance payments at the social security office on Wingewarra Street.

Epilogue

Go read the note. Tell me she’s not saying what I think she is: she regrets not having lined the kids up against the rainwater tank. I want to believe it’s not true. I know it is. I was right to protect those little kids all along – I knew she wasn’t safe. Little ones, I tried but I was just a kid myself.

Laura, this is heartbreakingly sad. I want to tell that 7-year-old she is amazing. And so are you now. Thanks for all you do.